Le Doux Payis, 1882

Pouvis de Chavannes (1824-1898)

25.7 x 47.6 cm, New Haven (CT), Yale University Art Gallery

The Mary Gertrude Abbey Fund (1958.64)

“Figures in Reverie, Revered Figures”. Il titolo del mio saggio fa gioco su due parole la cui fonetica è simile, ma le cui origini etimologiche sono diverse. Il sostantivo “reverie”, migrato dal francese antico all’inglese medievale, descrive uno stato di meditazione o il perdersi nei propri pensieri — la condizione che meglio descrive le figure dipinte di Pasquale Celona. Il verbo “revere” deriva dal latino “revereri”, che significa rimanere in ammirazione di qualcuno o qualcosa — e questo termine ci fa pensare alla venerazione di Celona per la tradizione artistica che egli stesso perpetra. Nel gioco di parole di questo mio titolo, ovvero nella curiosa associazione fonetica delle parole “reverie” e “revered”, possiamo scorgere l’artista, l’uomo che porta figure da sogno di tradizione artistica vicino all’immaginazione, alle divagazioni della sua mente, per creare qualcosa di nuovo. Attraverso i suoi dipinti, dunque, l’artista ci dona il suo mondo.

L’universo pittorico di Celona attinge da diverse fonti storico-artistiche. Nei suoi lavori il colore è luce e la luce è l’elemento fondamentale. Anche la linea gioca un ruolo. Tuttavia, la linea è un accessorio agli effetti di luce poiché la linea si muove sempre al ritmo della sinfonia di una luce colorata che si origina in ogni tela. A veicolare simpatia, ovvero attrazione visiva ed emozionale, è soprattutto la figura femminile. Anche in questo senso il mondo dipinto dall’artista è al tempo stesso antico e nuovo: il nudo femminile, infatti, è stato cardine della pittura fin dal Rinascimento. Celona attinge dal nobile passato del nudo nell’arte, ma nelle sue mani il nudo diventa il soggetto centrale di una nuova realtà pittorica, una dimensione che alcuni potrebbero voler definire “postmoderna”.

Il Postmodernismo ha avuto inizio come stile di pittura nel periodo in cui Pasquale Celona riceveva il Premio “Il Leone d’oro” del Circolo della Stampa a Firenze, nel 1978. In effetti l’opera dell’artista si rispecchia nella combinazione di stili e nel gioco di significanti che caratterizza il Postmodernismo quale corrente. Nondimeno, il fare di Celona trova origine nella sensibilità affatto particolare di questo artista. Anche se l’inizio del suo excursus nella pittura coincide con l’avvento del Postmodernismo quale stile, direi che questa coincidenza è più accidentale che frutto di intenzione. Pertanto, seppure il Postmodernismo possa rappresentare un “facile perno” su cui “incardinare” lo stile dell’opera di Celona, ritengo più opportuno focalizzarsi sull’artista stesso, sulla sua identità e sulla sua personalità.

Nato in Calabria e trasferitosi in Toscana, Pasquale Celona ha abbracciato idealmente un ricco intreccio di atmosfere storiche e culturali in contrasto fra loro. Nel suo spirito come nella sua pittura egli ha intessuto questi contrasti creando opere d’arte perfettamente equilibrate (affascinanti e quiete). Nel cercare il tono, il tenore, il fulcro del suo universo pittorico, ci imbattiamo inevitabilmente nella combinazione delle parole “reverie” and “revered” [nel saggio originale in inglese], parole che risuonano come un’eco nella realtà remota e incantevole dell’artista, un mondo che è estasi dell’immaginazione.

Il dipinto raffigurante Figure sulla spiaggia del 1985 è piena espressione dell’immaginario di Pasquale Celona. Tre figure femminili evocano il tema classico dei tre stadi della vita. La figura più piccola, al limite dell’istmo su cui siede, si affaccia all’orizzonte. La sua distanza dall’osservatore nello spazio visivo implica una distanza nel tempo, dunque questa figura rappresenta l’infanzia. La posizione supina della gigantesca figura sulla destra, drammaticamente scorciata, potrebbe simboleggiare una persona vicina all’esperienza della morte – così come s’intendono le figure che sovrastano un monumento funebre.

Une baignade à Asnières, 1884

Georges Seurat

Olio su tela, 201 x 301.5 cm

Londra, National Gallery (NG3908)

In ogni caso la figura in questione parrebbe essere in uno stato contemplativo, perduta nei suoi pensieri. Non è possibile stabilire se i suoi occhi siano aperti o chiusi e questo particolare, così come suo corpo dall’aspetto androgino, lascia spazio all’ambiguità. La figura sulla sinistra, disposta nella classica posa di tre quarti, ha un seno ampio e un addome pronunciato, a suggerire forse la fecondità associata alla giovinezza e alla precoce età adulta. Il tema dei tre stadi della vita parrebbe essere qui raffigurato in modo tale che sia possibile coglierlo per intuizione, piuttosto che prendendo atto di una rappresentazione visiva più esplicita. Questo tipo di istanza aperta alla mutevolezza dei significanti ben si accorda con il Postmodernismo. Nondimeno, il colore e il suo ruolo quale luce lega le figure all’eterno mito dell’arcadia come in una sinfonia pastorale che permea una terra di delizie remota quanto mirabile. La tavolozza di Celona è la materia dei sogni: i suoi colori evocano canditi dalle tinte pastello e dolci di ogni tipo, abiti da festa con la morbidezza del tulle, ma anche la sabbia, il mare e il cielo di isole lontanissime. La languidezza delle figure, la loro interiorità e la loro completezza rendono ancor più evidente, a livello percettivo, una distanza dalla quotidianità della vita reale. Le linee, sinuose e fluide, e l’uso sapiente del colore rivelano la scioltezza del gesto pittorico.

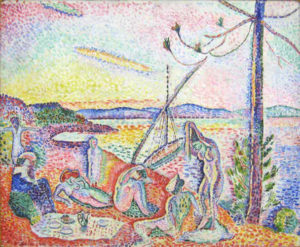

Per evidenziare il relazionarsi di Pasquale Celona alla tradizione artistica e così pure al tema dell’arcadia si possono ricordare solo alcuni dipinti noti ispirati a canoni moderni. Primo fra tutti Le Doux Pays di Puvis de Chavannes del 1882. Come non menzionare inoltre Un Baignade à Asnières, la grande visione di una pastorale senza tempo nell’età industriale fissata sulla tela da Georges Seurat nel 1882. Infine Luxe, Calme et Volupté di Henri Matisse del 1904-1905 con il suo pendant, Joie de Vivre, del 1905-06. Le pitture di Celona, e in particolare l’opera testé descritta, condividono con queste opere di grandi Maestri l’atmosfera di un mondo di fasto e abbondanza. In Figure sulla spiaggia l’incontro fra la terra e il mare, la posizione delle figure sulla riva e le barche placide sull’acqua ricordano Puvis e Seurat. Nondimeno, la costruzione delle figure attraverso linee sinuose, il riecheggiamento di questa linearità in tutti gli elementi della pittura e il senso di fluttuazione in un mondo stabile ricordano la gioia e la facilità voluttuosa di Matisse.

Osservando la tela di Celona sovviene alla mente L’invitation au voyage di Charles Baudelaire, il poema che ha ispirato Matisse a realizzare l’omonimo dipinto del 1904-1905.

In effetti nell’immagine fissata dall’artista sulla tela si respira un’atmosfera di lontananza. Tuttavia, è presente in quest’opera anche un richiamo alla vita: la terra, il mare, il cielo e i loro colori parrebbero evocare i l’infanzia di Pasquale in Calabria, trasfigurata così come può esserlo nella memoria e nei sogni di qualcuno che in quella regione del sud Italia ha vissuto tempo addietro. L’inclusione di un ricordo particolare all’interno di una rappresentazione “arcadica” è una sorta di gesto postmoderno di per sé. Piuttosto che con questa modalità, tuttavia, in questo lavoro Celona comunica attraverso la pittura in una maniera più delicata, più gentile, offrendo una visione individuale all’interno della tradizione moderna di rappresentazione dell’età dell’oro. Un rapporto con l’arte del passato si evince anche nei dipinti di Pasquale Celona che ritraggono un’unica figura o il tema della maternità. La Maternità del 1981 raffigurante madre e figlio evoca le rappresentazioni rinascimentali della Madonna col Bambino. In questo dipinto Celona abbandona le linee sinuose in favore di una costruzione formale in cui prevalgono spigolature. Questo giocare con la costruzione Cubista è addolcito dalla resa naturalistica dello spazio circostante nonché dell’alto schienale rettangolare della seduta e l’uso di lievi sfumature cromatiche per delineare la transizione tra il pavimento e la parete sullo sfondo. La rotondità dei volti della madre e del figlio così come del seno della madre fa da contrappunto alla spigolosità dei corpi. Ancora una volta, la luce è colore nel dipinto. La tavolozza ha perso la sua bellezza fantasiosa e il colore è ora permeato più di memoria storica che di sogno. Non si può non cogliere l’affinità tra la tavolozza del nostro artista e quella che fu di Piero della Francesca. La figurazione e i colori del Maestro del Quattrocento sono espressione di un naturalismo che ancora oggi induce l’osservatore a relazionare la visione pittorica a quella della vita reale e, al tempo stesso, a varcare i confini dello spazio di osservazione per “entrare” in quello del dipinto. Tutto ciò si ritrova nella pittura di Pasquale Celona.

Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1904-05

Henri Matisse (1869-1954)

Olio su tela, 98 x 118 cm

Parigi, Musée d’Orsai (DO 1985 1)

Nella sua Maternità il “tappeto” verde svolge un ruolo chiave poiché esso cattura visivamente l’osservatore indirizzando il suo sguardo verso le figure così da attrarlo nel mondo raffigurato dell’artista. All’epoca di Piero della Francesca la pittura raccontava la storia cristiana a coloro che non sapevano leggere e dunque non avevano accesso alle sacre scritture. La narrazione avveniva attraverso il medium visivo, ma la rappresentazione doveva altresì trasmettere un messaggio trascendentale, dunque al di là del visibile. Lo scopo della pittura era quello di invocare un regno angelico, lo spazio sacro che poteva solo essere immaginato o ricreato mediante intervento soprannaturale. La Maternità di Pasquale Celona ci invita a distaccarci dalla dimensione del reale per avvicinarci ad altro, ma non è chiaro se la dimensione che egli evoca sia a tutti gli effetti uno spazio del sacro. La mente è il fulcro del mondo pittorico dell’artista: è attraverso la mente e l’immaginazione, ancor prima che attraverso il gesto pittorico, che Celona ha dato forma alle figure della madre e del bambino ossequiandole nel suo fare. In questo processo creativo l’artista ha preso spunto dal tema della Madonna col Bambino, ma tentando di dar vita a qualcosa di diverso dall’archetipo. Tutto questo per dire che il mondo dipinto di Pasquale Celona racchiude in sé, almeno in parte, la storia della pittura. Al tempo stesso occupa, all’interno di essa, un proprio spazio — una nicchia in cui si dà il via a un gioco postmoderno di significanti, seppure esclusivamente per rimarcare un distacco dal Postmodernismo. La Maternità di cui si è detto non soltanto coinvolge l’osservatore in un gioco interpretativo, ma offre spunti di riflessione su aspetti diversi quali l’androginia e l’ambiguità, i passaggi dal naturale all’artificiale (o pastorale), dal reale al sogno, dal profano al sacro. Questo particolare dipinto, inoltre, dialoga con una tradizione artistica di riferimento reinterpretando, con una sensibilità nuova e contemporanea, i temi che a quella tradizione appartengono.

Esempio eclatante di tutto ciò è la Figura assisa in un campo di narcisi sulla quale si staglia un cielo immenso, all’apparenza infinito. La figura femminile col mento appoggiato sulla propria mano è da sempre emblema di melancolia o acedia (si pensi all’incisione di Albrecht Dürer Melencholia I del 1514. Più comunemente questa stessa postura è associata al sognare a occhi aperti, ma in ogni caso suggerisce uno stato meditativo. Senza ombra di dubbio questa soluzione compositiva trova origine nella tradizione iconografica testé accennata, e tuttavia un sottile gioco di forme nel corpo della figura parrebbe suggerire contestualmente anche un altro significato. Più si osserva la mano su cui la figura nuda dipinta da Celona poggia il mento, più questa mano appare estranea al corpo della stessa, quasi come se la mano divenisse una sorta di plinto. D’altro canto il volto della figura nuda, che a un primo sguardo appare unito al collo e al corpo della stessa (così come deve essere) sembra quasi fluttuare, a dispetto dell’anatomia, e trasformarsi in una scultura a sé stante, poggiata sul “plinto” ideale costituito dalla mano. A enfatizzare il gioco di significanti in questo lavoro è l’aspetto e la composizione per piani del volto, che ricorda una maschera Grebo nonché alcune composizioni di Picasso, ma anche Brancusi e persino Naum Gabo. Una maschera nasconde il volto, ma al tempo stesso rivela il carattere della figura che la indossa. Il carattere della Figura assisa in un campo di narcisi dipinta da Celona è ambiguo fors’anche perché il suo volto-maschera è espressione, se non del carattere del soggetto, di uno stato interiore ben più intelligibile al tempo di Dürer che nell’età contemporanea. Inoltre, come già osservato, la posa della figura è ambigua poiché oltre alla melancolia può anche alludere a un sogno a occhi aperti. Andando ad aggiungere un altro “anello” alla nostra “catena” interpretativa, vale la pena rilevare che il magnifico connubio di toni arancio e blu in questo olio su tela porta l’osservatore a spaziare nella scala sensoriale orientandosi, per così dire, in due direzioni: la combinazione di arancio e blu evoca da un lato la meravigliosa cacofonia dei cromatismi di Vincent van Gogh, e da un altro lato la quieta ma vibrante atmosfera delle opere di Matisse.

La pittura di Pasquale Celona si colloca precisamente al confine liminale tra staticità e movimento, tra la melancolia e il silenzioso salto nel mondo dei sogni. Là dove il fantasticare a occhi aperti si fonde con un senso di ammirata riverenza prende vita l’opera di questo autore. Guardando con venerazione a una grande tradizione artistica, egli trae ispirazione dalle fonti del passato. Al tempo stesso, affidandosi all’immaginazione e alle divagazioni della mente, egli colloca la sua pittura entro una tradizione artistica di riferimento ma trasforma quella stessa tradizione aprendo un varco al gioco di significanti. E attraverso il suo fare dà la sua impronta distintiva a tradizione artistica e significato della rappresentazione. Tutto questo è il mondo dipinto di Pasquale Celona.

FIGURES IN REVERIE, REVERED FIGURES:

PASQUALE CELONA’S PAINTED WORLD

by Karen Lang

Figures in Reverie, Revered Figures. The two parts of my title hinge on words with an acoustic similarity, though the origins of these words are separate. The word ‘reverie’ journeyed from the Old French to the Middle English to denote the state of musing or being lost in thought — the state that best describes Pasquale Celona’s painted figures. The word ‘revere’ comes from the Latin word ‘revereri,’ meaning to stand in awe of — this word reminds us of the esteem in which Celona holds artistic tradition. In the hinge of our title, in the playful acoustics of ‘reverie, revered,’ we find the artist himself, the man who brings the revered figures of artistic tradition into proximity with the reveries of his mind and imagination to create something new. This is also to say that in these paintings, the artist has given us his world.

Celona’s painted world draws on various art-historical sources.In these works, colour is light and light is the keynote. Line also plays a role. In every case, however, line is an accessory to the effects of light, for line moves to the rhythm of the symphony of coloured light created in each canvas. The main vehicle of sympathy — of visual and emotional attraction — is the female figure. In this sense, too, Celona’s painted world is as old as it is new: the female nude has been a centrepiece in painting since the Renaissance. Celona draws on the revered past of the nude in art, but in his hands the nude becomes the centrepiece of a new — some may want to call it ‘postmodern’ — painted world.

Postmodernism began as a style in painting around the time Celona received the Premio Il Leone d’oro by the Circolo della Stampa, Firenze, in 1978. Celona’s sensibility is attuned to the mixing of styles and the play of meaning that characterise postmodernism as a style. And yet Celona’s painted world is also stamped through his distinct sensibility. Though Celona’s painting coincides with the rise of postmodernism as a style, I would say that this coincidence is more adventitious than fruitful. While ‘postmodernism’ provides us with an easy peg on which to hang the style of Celona’s work, we would do better to focus on the artist himself.

Born in Calabria and domiciled in Tuscany, Celona’s spirit has embraced a rich tapestry of historical, cultural and atmospheric contrasts. As in his spirit, so in his painting, the artist has woven these contrasts into perfectly poised (lush and quiescent) works of art. If we were to seek the tone and tenor, the pivot, of this painted world, we would encounter our acoustic word play once again: Reverie, Revered, the sonic echo of a distant and delightful land, one in rapture to the imagination. Celona’s multi-figured painting of 1985, Figures on the Beach is an integral expression of his painted world. Three female figures suggest the classic theme of the three stages of life. A diminutive figure peers over land’s end toward the horizon. Placed at the furthest distance from us to imply her removal in time, this figure represents childhood. The supine pose of the gigantic, dramatically foreshortened, figure at the right may symbolize death — as does the figure atop a funerary monument. At the same, this rather androgynous figure could be musing, lost in thought. In the final analysis, it is impossible to tell whether the figure’s eyes are open or shut. Akin to the androgynous body of the figure, this masterful detail opens the space for ambiguity. The figure at the left, posed in classic three-quarter view, presents her ample breasts and somewhat swollen abdomen to the viewer, thereby suggesting pregnancy or, at the very least, a quality of fecundity associated with youth and young adulthood. The classic theme of the three stages of life seems to be visually evident in the painting and yet it lingers as an intuition rather than a fact. This instance of the mutability of meaning chimes with postmodernism.

At the same time, colour and its role as light tie the figures to the enduring myth of arcadia as a pastoral symphony, as a distant and delightful land. Celona’s palette is the stuff of dreams — his colours suggest pastel candies and confections of all kinds, tulle and party clothes, the sand, sea and sky of faraway islands. The languor of the figures, their interiority and their completeness, underscores their distance from the actual, everyday world. Line, sinuous and fluid, works with colour to suggest ease. One has only to recall a few well-known paintings in the modern canon to make the point of Celona’s relation to artistic tradition and the theme of arcadia: Le Doux Pays, Puvis de Chavannes’ canvas of 1882; Un Baignade à Asnières, George Seurat’s enormous industrial vision of a timeless pastoral of one year later; finally, Henri Matisse’s Luxe, Calme et Volupté of 1904-05 and its pendant, Joie de Vivre, of 1905-06. Celona’s painting partakes of these timeless worlds of luxury and abundance. The joining of land and sea, the positioning of the figures at the water’s edge, and the tranquil sailboats on the water, recall Puvis and Seurat. The construction of Celona’s figures through sinuous line, the echo of this line throughout all the elements of the painting, and the feeling of floating within a nonetheless stable world, is reminiscent of the joy and voluptuous ease of Matisse. Celona’s painting also reminds us of Baudelaire’s L’Invitation au Voyage, the poem which inspired the title of Matisse’s painting of 1904-05. If the mood here is faraway, there is nonetheless a relation to life in Celona’s painting: land, sea, and sky, their colours and even their mood, seem to tell of a childhood dream of Calabria, of the south of Italy, as this now exists in the memory of one who had lived there long ago. The nesting of a particular memory within a diffuse and generalising depiction of arcadia is a kind of postmodern gesture of its own. Rather than announce itself as such, however, Celona’s painting speaks more softly, more gently, as an individual vision within the modern tradition of the depiction of the Golden Age. A relation to the art of the past also suggests itself in the paintings of single figures and of the mother and child. A painting of 1981 of a seated mother and child, Motherhood, calls to mind Renaissance depictions of the Madonna and Child. In this painting, Celona abandons sinuous line in favour of a building up of figures and forms through predominately angular facets or wedges. This play with Cubist construction is softened by the naturalistic rendering of the surrounding space, including the rectilinear high back of the chair and the use of subtle differences in colour to mark the transition between the floor and the rear wall.

The roundness of the faces of the mother and child, and of the mother’s breasts, provides a counterweight to the angularity of their bodies. Once more, colour is light in this painting. The palette has lost none of its fanciful delight, but colour is now less the stuff of dreams than it is the stuff of history: one cannot help but feel the affinity between Celona’s palette and the Quattrocento painting of Piero della Francesca. Piero’s figures and his palette are just this side of naturalism, close enough to invite us to relate his painted world to the world of real life yet distinct enough to prompt us to follow the painting along its passageway from our space to its own world of depiction. Celona’s painting shares this quality. In his painting, the green carpet plays a key role, beckoning us visually and figuratively to enter along the passageway into the artist’s painted world. In Piero’s day, painting revealed the Christian story to those who could not read the words of Scripture. Meaning had to be conveyed visually but this visual world also had to convey meaning beyond the visual. The purpose of painting was to invoke the angelic realm, the sacred space which could only be conjured or imagined. Celona’s painting beckons us to take leave of this world for another one, but it is unclear whether the other world is, strictly speaking, a sacred space. Once again, the artist’s mind is the pivot of the painted world: mind and imagination have intervened to shape the figures of the mother and child and to lend to them their reverie; these forces have also drawn in reverence upon the depicted theme of the Madonna and Child to create something new from it.

All this is to say that Celona’s painted world partakes of the history of painting but it creates its own space in relation to it — a space which opens a postmodern play of meaning only to mark its distinction from postmodernism. Celona’s painting not only opens a play of meaning: we have touched onandrogyny and ambiguity, on passages from the natural to the artificial (the pastoral), from the real to the dream, and from the secular to the sacred. This painting also opens artistic tradition by bringing its themes into proximity with a new, contemporary sensibility. Nothing suggests this better than the Nude Seated against a Field of Daffodils crowned by an enormous, seemingly endless, expanse of sky. The figure cradling her jaw is a timeless emblem of melancholia or acedia (Dürer’s etching, Melencholia I, of 1514 is a primary example). More commonly, this pose is equated with reverie. Either way, whether indicating melancholy or reverie, the pose of the figure suggests an inward state. Celona’s figure resides unmistakably in this iconographic tradition and yet a subtle play with the body of the figure suggests another meaning at the same time. The longer we look at the hand which cradles the jaw of Celona’s nude, the more it unhinges itself from the body to become a kind of plinth. For its part, the face of the nude, which initially appears attached, and properly so, to the neck and body, seems to float free of anatomy to become a freestanding sculpture resting on the ‘plinth’ of the hand. The mask-like quality and planar construction of the face, reminiscent of the Grebo mask and of Picasso’s construction, but also of Brancusi and even Naum Gabo, underlines the play with meaning. A mask conceals the face but it also reveals the character of the figure beneath. In Celona’s painting, the figure’s character (or to invoke the expression used in Dürer’s time, the sign under which she has been born) is ambiguous. And not only the figure’s mood is ambiguous. Let us recall that her pose not only evokes melancholy, it also suggests reverie. To add another link to our chain, we can note that the painting’s magnificent marriage of orange and blue can also go either way on the scale of feeling: the combination of orange and blue conjures up the marvellous cacophony of Van Gogh’s chromatics and the soothing, yet invigorating, atmosphere of Matisse. Celona’s painting is poised precisely at the hinge between rest and movement, between the immobility of melancholy and silent leap of reverie. At the hinge of reverie and revere lies Celona’s painted world. Standing in awe in front of a revered artistic tradition, the artist draws upon the wellsprings of the past. Relying upon the reverie of his mind and imagination, he sets his painting within artistic tradition but he transforms tradition by opening it up to a play of meaning. At the same time, he gives tradition and meaning his own distinctive stamp. This is Pasquale Celona’s painted world.